| |

FIG PUBLICATION NO. 29

Business Matters for Professionals

A Guide to support professionals in the task of business

management

CONTENTS

Preface

Foreword

Checklists for the business

- Introduction

- The Business Context

2.1 Subject Matter

2.2 The Business

2.3 Society and the State

2.4 The Business, Society and the State

2.5 Consequences

2.6 Summary

2.7 Checklist

2.8 Bibliography

- Business Planning

3.1 What is business planning?

3.2 Strategic Planning

3.3 Tools

3.4 Operational and Business Planning

3.5 Measuring performance

3.6 Summary

3.7 Checklist

3.8 Bibliography

- Quality and Customer Service

4.1 What is quality?

4.2 The cost of quality

4.3 The customer and quality

4.4 Customer Service Charter

4.5 Quality Assurance

4.6 Summary

4.7 Checklist

4.8 Bibliography

- Professional Ethics

5.1 What are ethics and why are they

important?

5.2 Ethical principles

5.3 A code of conduct for the business

5.4 Preparing the firm and staff

5.5 Summary

5.6 Checklist

5.7 Bibliography

- Managing Information and Information

Technology

6.1 Managing Information

6.2 Managing information technology

strategically

6.3 Checklist

6.4 Bibliography

- Other Issues

7.1 Governance

7.2 Staff

7.3 Legal issues

APPENDIX

Orders of the printed copies

Who can argue that business doesn't matter? All of us, one way or

another, are trying to ensure the success of one or more organisations. It

is through our organisations that we create the resources necessary and

important to us as individuals and to society. Business, however, is often

seen as a pejorative form by professionals, including surveyors, whose

pursuit is of higher values like accuracy, elegance and balance.

Over the last decade FIG, and in particular its Commissions 1

(Professional Standards and Practice) and 2 (Professional Education), has

been working in the area of business and management, and attempting to link

them more clearly to the realm of professional surveyors. This has already

resulted in FIG Publications covering Ethics (No 17) and Continuing

Professional Development (No 15).

Many of FIG's 250,000 individual members work in sole practices,

partnerships or other small and medium enterprises. In such environments,

business and management matters become particularly crucial, and the

expectations of customers, society and governments continue to rise.

I am therefore pleased that FIG is able to add this Guide to its

collection of publications. It is another element in FIG's ongoing work in

this area, and plans are already in place to build on it. The Guide will be

of use to many individuals and organisations, within and beyond the FIG

community. I commend it to you, and thank all who contributed in its

creation, particularly the authors Iain Greenway (Ireland),

Michael Keller (Switzerland), Tom Kennie (UK), Leonie Newnham

(Australia) and John Parker (Australia).

Robert W. Foster

President, FIG

Business Matters for Professionals

A Guide to support professionals in the task of business

management

The FIG Commission 1 Working Group 2 on Business Practices

Iain Greenway, United Kingdom

The International Federation of Surveyors FIG

FIG Commission 1 (Professional Standards and Practice) has

developed this Guide to provide advice to surveyors in running businesses. It is

particularly targeted at individuals starting up in business but it will also

provide a useful source of information to those already responsible for a

business. Although the Guide is primarily focused on the issues facing private

businesses, much of the content will be very relevant to public sector

operations, particularly those operating as quasi-businesses with identifiable

customers. If there is a demand, further Guides will be produced, tailored to

different business sectors.

The Guide is designed to be of use around the world. It does not

pretend to cover the detail of issues in every country and region: instead, the

Guide highlights particular topics that a business needs to address, provides

frameworks for doing so and suggests sources of additional information. The

Guide also incorporates as reference material the FIG Charter for Quality and

the FIG Statement of Ethical Principles and Model Code of Professional Conduct,

and makes reference to some other key documents.

The Guide is structured with a brief introduction followed by

two overview chapters, one covering the context of a business and the other

overviewing business planning issues. Further chapters deal with particular

topics, and a checklist summarises the key elements which a business should

ensure that it has in place. Each of the chapters is designed to be

self-standing whilst still building to a coherent overall picture.

The Guide builds on the work of a Commission 1 Working Group led

by Chris Hoogsteden which produced the paper 'Management Matters' at the

XX FIG International Congress held in Melbourne in 1994, and on work between

1994 and 1998 led by Ken Allred (on ethics) and John Parker (on

quality).

Inevitably, the Guide will create questions as well as provide

answers. An early port of call for such questions should be the relevant

national professional association/ institution, which will generally have

material or advice relevant to the particular country and discipline.

Chapter 2: The Business Context

- At an early stage of setting up a business, review the interests

and power of primary and secondary groups which may impact on the

business (section 2.4)

- Ensure that this analysis inputs fully to the business planning

process

- Monitor changes in interests, groupings and relative power, and

factor these into ongoing planning (section 2.5)

|

Chapter 3: Business Planning

- Ensure that your organisation has a structured, regular approach

to strategic and operational planning which involves all staff and

which delivers clear objectives (section 3.1)

- Ensure that the strategic planning process explicitly reviews

the aspirations of each owner/ director/ senior partner with regard

to the company, to ascertain that all key players wish to move in

approximately the same direction at approximately the same speed

(section 3.2)

- Place individual responsibility against the achievement of each

target associated with the objectives (sections 3.2 and 3.4)

- Regularly monitor progress towards the targets, taking early and

decisive action where necessary (section 3.5)

- Consider how best to link individual staff appraisal and reward

systems to the successful delivery of the organisation's objectives

(section 3.4)

|

Chapter 4: Quality and Customer Service

- Create an environment of quality and customer service and

continuously review how to embed this in the business (section 4.3)

- Ensure that all staff are adequately trained (section 4.3)

- Document key processes and ensure that staff follow them; this

will ensure consistency of activity and of output, providing

assurance to customers (section 4.5)

- Undertake customer surveys to determine their needs and

expectations so that the business can plan to meet and exceed them

(section 4.4)

- Continually review all activity to ensure best practice,

involving staff and customers in this process

|

Chapter 5: Professional Ethics

- Create an initial code of conduct for the firm as soon as you

start to build the firm. Use frameworks available from national

survey associations and other firms but tailor them to your firm and

its circumstances (section 5.3)

- Continually test the code against situations that you are likely

to encounter, and develop it as necessary. Do this thoroughly at

least once a year

- As part of staff development processes, discuss ethical dilemmas

to ensure the conformance of individuals with the code (section 5.4)

|

Chapter 6: Managing Information and Information

Technology

- Identify the application systems of importance to the

organisation and ensure that they are managed and maintained to

provide ongoing business support and that they can be supported into

the future

- Assess the need and potential for integration of multiple

application systems so as to streamline business activity, and the

possible challenges offered by technological developments; build

this into business planning activity (section 6.2)

- Ensure that clear organisational policies and standards shape IT

developments and investment, and that staff are trained in the

skills necessary to make best use of the systems

- Rigorously review business drivers (i.e. identify which business

objectives are driving the project) before committing (section 6.2)

- Assess the scope of any IT project before commencing investment,

to ensure that it is appropriate to the business's aims and that the

aims are deliverable (section 6.2)

|

Chapter 7.1: Governance

- Determine at an early stage the appropriate arrangements for

external 'reality checking' of strategic decisions, and ensure that

these conform with legal requirements

|

Chapter 7.2: Staff

- Set down employee development and remuneration policies that

meet staff's realistic expectations and business needs

- Ensure that new recruits will match business needs and fit with

the business ethos

|

Chapter 7.3: Legal Issues

- Investigate and monitor legal and official standards relevant to

the business, calling on professional associations for guidance

|

Technological and social changes require changes in business and

in management. It is generally agreed that the rate of external change is

increasing. The change impacts on surveying businesses as much as it does on

other businesses. The education and training of surveyors (of every discipline),

however, continues to give a good deal of time to technological developments and

their impacts, but less time to the changing challenges of management. The need

for all-round skills in management and business is brought into stark relief for

surveyors running small companies, where they will often be unsupported by

experts and where advice from professional consultants may be beyond budgetary

reach.

A key change for survey businesses in recent years is that

members of the public have an increasingly high expectation of professional

service providers. Professionals are expected to be fully accountable for their

advice and willing to tailor that advice to particular circumstances. Society is

also increasingly demanding, believing that a key differentiation of

professionals from others is a professional's ability and duty to consider the

needs of wider society as well as of the client, and to be able to deal with

this balance successfully.

Further changes in the business environment include:

-

The growth of the power (and respectability) of pressure

groups, adding complexity to the balance that has to be struck by

professionals;

-

The intertwining of different professions, in large part

due to technological developments, meaning that a professional is

expected to have a base knowledge of a number of professions;

-

The immediacy and reach of communication tools, allowing

and requiring rapid decisions by businessmen;

-

An increasing globalisation, requiring managers to

understand regional differences in culture, people and law; and

-

An increasing intolerance by many governments of

self-regulation by professionals.

These changes put additional pressures on a professional

surveyor in the dual roles of expert and businessman. Neither of these roles

can be ignored, and the abilities of an individual in each of them will

continually be challenged. A professional surveyor will, in most cases, have

a personal interest in the content of his or her work, and a passion to do

it to the best of his or her ability. Business challenges, however, are also

a necessary part of an increasing number of professionals' lives.

Professionals will often have received limited training or experience in the

business aspects of their work, and may have limited interest in them - they

will often be viewed as a means to an end. This Guide is designed to assist

professional surveyors to fulfil this vital part of their responsibilities.

This chapter summarises the third-party interests to be

taken into account in the running, and more particularly in the setting-up,

of a company. A company is embedded in a network of social expectations and

state regulations. These have to be appropriately factored into business

decisions, if the company's long-term survival and flourishing is not to be

jeopardised.

In general terms, a business strives (in the short term) to

make a profit. In addition, it wants (in the long term) to ensure its

ability to survive.

In order to achieve these aims, a business will, in concrete

terms:

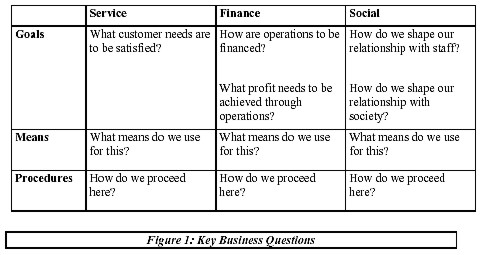

A successful business will give consideration to three key

areas, namely:

-

Service;

-

Finance; and

-

Social.

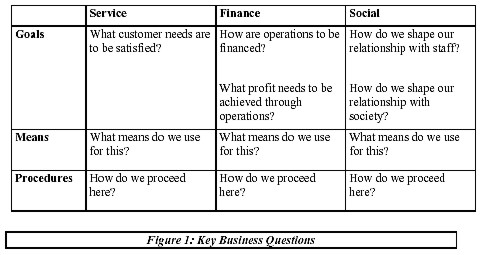

The questions to be answered by every business are outlined

in Figure 1.

Later chapters in this Guide address these questions

further; the remainder of this chapter considers further the relationship

between business and society.

Society is a structure of conflicting interest- and

power-groups (associations, political parties, the press, trade unions,

economic enterprises, etc.). These groups surround individual businesses.

The need for the State as a regulating authority emerges from the conflict

between group interests. The State must above all ensure three things:

-

The interests of a society must be channelled and

coordinated by the State: the assertion of social interests must be

ensured;

-

In regulating conflicting interests, the State must seek

a just balance between the different needs: there must be no arbitrary

choice of social interests; and

-

The rules of behaviour which have been created must have

a reliable chance of being asserted - compulsorily, if need be: the

State must set appropriate legal norms.

Thus, the State decides:

-

Which social interests are enshrined in laws and

compulsorily asserted, through the power of the State if need be

(Courts, compulsory execution, Police); and

-

Which social interests are excluded from assertion by

the State.

The next section reviews the key relationships between a

business, society and the State. These relationships will differ between

countries and in particular between types of economic tradition. In market

economies, the State will generally only 'interfere' where there is a proven

need for it to do so, whereas in centralised economies the State will take a

much larger role in regulating society.

All enterprises and entrepreneurs strive towards goals which

they hope to achieve through their entrepreneurial activity. On the one

hand, these goals emerge from answering the questions in Figure 1. Usually,

however, additional goals are also pursued, such as ensuring the living of

the entrepreneur and his or her family, prestige, having the guts to take

risks, independence, etc.

The personal interests of the entrepreneur will at times

come into conflict with various social interests. All of these interests

must be analysed and taken into account in business decisions. Since all

entrepreneurial activity takes place within a social environment, the

business is also dependent upon society. Correspondingly, society makes

demands on entrepreneurial activity.

The following interests are of paramount importance for

enterprises. These groups directly determine a business's short-term success

or failure:

-

Customers;

-

Staff;

-

Suppliers;

-

Investors; and

-

Competitors.

Suitably taking into account the interests of the following

secondary groups is of crucial importance for the long-term survival of a

business:

Both the primary and secondary group interests must be taken

into account in the basic organisation of a business. No business survives

in the long run if it fails to establish a harmonious relationship with

these group interests, and does not bear in mind at least certain aspects of

these interests when formulating its business strategy.

The secondary groups' interests may be enshrined in laws and

then asserted by the State. In this case, businesses must always adhere to

the relevant behavioural standards if they are not to risk State sanctions

(fines, penalties, suspension of trading, etc.).

Issues relevant to various groups are:

-

Environmental protection associations: banning of

products, banning of certain production techniques, banning of certain

emissions, restriction on choice of location, restrictions on

construction activity.

-

Trade Unions: adherence to minimum wages and

maximum working hours, holidays, social -security, provision for

sickness, accident and death, restrictions on dismissals, restriction of

work allocation, monitoring of business decisions by staff and staff

representatives.

-

Employers' associations: professional rules,

production and other standards, obligation to inform.

-

Press and Media: monitoring of business activity.

-

Consumer protection associations: obtaining

trading and operating approval, rules on product safety, product

liability, restrictions on advertising.

-

Churches: tax liability, holidays.

-

Military: controls or bans in safety-relevant

areas, export bans, compulsory production.

-

Other public interests: requirement for building

and operating approval, restriction of construction activity, ban on

unfair competition, ban on cartels, obligation to inform, company law

regulations, social security contribution and tax liabilities, adherence

to health regulations.

In light of the above, it is vital to consider State and

social interests at an early stage of business planning, since they will

always limit the autonomy of a business and must therefore be taken into

account by the business in a suitable way. The extent to which this is true

for any group or issue depends on the relative importance of the interests:

State interests must always be taken into account, but social interests need

be considered only when they have a certain strength and significance.

Since State and social interests may change over the course

of time, they must repeatedly be analysed and taken into account at regular

intervals: State interests may disappear, and the significance of social

interests may change with the passage of time.

The consideration of State and social interests is less

difficult when a business limits its activities to a single country or

culture group. It is then active in a familiar and homogenous environment.

Careful analysis of the State and social interests should then be a

relatively simple matter. When a business decides to become active in

several countries or culture groups, however, the analysis becomes a great

deal more difficult. In such cases, a business has to analyse the social and

State interests for each State.

Social and State interests mark out the sphere of autonomy

for a business. Careful analysis for these interests and their consequences

for the business is vital, particularly when a business is being set up,

since mistakes in the analysis of these interests, or the omission of this

analysis, is likely to have severe consequences for entrepreneurial

activity. In addition, it is essential for the analysis to be carried out

for each individual State or culture in which the business operates (or

plans to operate). The analysis must be repeated at regular intervals as the

power of different groups will alter over time. Chapter 3 provides planning

frameworks which can be used to factor these interests into business

decision making.

-

At an early stage of setting up a business, review the

interests and power of primary and secondary groups which may impact on

the business

-

Ensure that this analysis inputs fully to the business

planning process

-

Monitor changes in interests, groupings and relative

power, and factor these into ongoing planning

The very general topics in this chapter are covered in the

initial sections of many of the texts referred to in the remaining chapters

in this Guide. There are no specific detailed references for the general

areas covered in this chapter.

Some would consider the process of developing a strategy as

a time-consuming distraction from the process of making money. For others it

is of critical importance to developing a successful business. This latter

group would argue that, in a business environment in which the rate of

change shows no sign of diminishing, the successful business needs to review

periodically its strategic direction and in light of that to develop more

detailed business planning.

A professional business has within it a portfolio formed

from the skills, knowledge and capabilities of its members. This mix

includes not only special professional skills and formal procedures, but

also intangible assets such as the business's presence and relationships in

key sectors, its reputation with clients or suppliers, and its 'culture' or

'ways things are done'. The match or otherwise of that mix of capabilities

to the market and the wider environment in which the business operates

determines its success or failure. A business's strategy, either explicitly

or implicitly, is the deployment of that capability mix in the wider

environment in which the business operates. It is often a product of past

successes and even the traditions established by the founder or founding

partners.

Business planning, therefore, is the art and practice of

examining the current fit of a business's capabilities to the environment

and adapting this as necessary. Owners and managers need to ensure that

adequate, shared intentions exist to keep the fit in the future. This may

mean deploying existing capabilities differently, and/or developing new

ones.

A multitude of models for the planning process exists; some

can be found in more detail in the references at the end of this chapter.

This chapter attempts to explain the process in a way that will be of

relevance for surveying practices.

We can consider planning for an organisation as addressing

four stages and generating four distinct outputs:

Business planning, although last in the sequence, is

particularly important since this is the process that coordinates the

resource requirements to achieve the Operating Plan. In many organisations,

two plans are produced - a Strategic Plan (including the corporate planning

elements) and an Operating Plan. This is the model used in this chapter. The

Strategic Plan may have a life of up to three years, whereas a new Operating

Plan will be needed each year.

A Strategic Plan will generally include:

-

A Mission Statement - this statement should, in a

small number of words, clearly identify why the organisation exists and

is the sole criterion by which the organisation's success should be

judged. The Statement should articulate the end result or outcome but

not normally the means by which the outcome will be achieved - this is

left to subsequent planning. The Mission statement is particularly

useful in focussing the efforts of the organisation.

-

Organisational Values - these express how the

organisation will conduct business; they address such matters as ethos,

culture, code of ethics, standards of behaviour, social justice,

environmental issues, social responsibilities etc. They should also

include staff development principles, and the approach to quality and

customers.

-

Organisational Vision - once the Mission and

Organisational Values have been decided, an Organisational Vision of

where the organisation wants to be in a given time frame needs to be

agreed. An appropriate time frame is of the order of five years for most

organisations. The Vision needs to be in outcome terms, that is, what is

to be achieved - usually addressing growth, market coverage, employee

involvement, product and service development, quality of product and

service, etc. The vision must be bold, setting a level of performance

that will stretch and motivate the organisation.

-

Organisational Goals - from the Vision, the Goals

need to be determined, again expressed in outcome terms. Usually six

goals are enough. Goals are aspirations of what the organisation wishes

to achieve. Again, they must set a level of performance that will

stretch and motivate.

-

Strategies - these are means not ends, and set

out (in general terms) how the goals will be achieved.

-

Objectives - these are determined from the

strategies adopted and are specific statements of the who, what and

when. The objectives need to be structured so that achievement of all of

the objectives will sum to the achievement of the goals. The objectives,

being specific, allow the creation of clear targets to allow monitoring

of organisational progress. These targets need to have individuals

explicitly accountable for their achievement, to ensure clear ownership

for delivery.

The list of references at the end of this chapter points to

examples of these components that can be found in various texts.

Setting aside time to plan the business's strategy and

development will inevitably be difficult to achieve during the normal Monday

to Friday schedule. Many businesses therefore find a one-day 'retreat',

preferably 'off-site', a suitable means for focusing on these key questions.

Key questions to be addressed in the strategic planning

process are:

Note: organisations may choose to define 'partner' for

these purposes in either the strict business sense or as a broader term

embracing all of the people key to the implementation of the strategy.

(a) Are the aspirations, abilities and relationships of

the existing owner(s)/ senior managers clearly understood?

-

Has each partner identified their personal aspirations,

and how they affect the business?

-

Does each partner appreciate the contribution of their

personal skills and capabilities to the business?

-

Do the partners appreciate the contribution each makes

to the success of the business?

(b) Is the current match of the business's capabilities to its market

understood?

- Is there a clear, shared, understanding of how the business's existing

capabilities serve its existing market: for example, what gives the

business its distinctive edge?

- Do the partners appreciate the dependence of that edge on their, and

others', skills and knowledge?

- What do the partners see as the critical success factors to delivering

the current business plan? Do they appreciate what provides their current

competitive advantage?

- What is the current financial situation of the business and its likely

earnings and investment requirements in the next three years?

- How might the business's market position be eroded in the future by

new competitors or new demands from the market?

- What does the business plan to do about any such erosion of its edge

in the market?

(c) Are the external trends that might affect the business's future,

identified and understood?

- Has the business considered, or researched, the likely changes in the

main markets for its products and services?

- Does the business have plans to improve its services, target new

markets, or change its share of existing markets? Does it have

confirmation that the anticipated demand for its services will exist?

- Are the business's plans translated into goals and targets (financial

or otherwise) which it aims to achieve in the next three years (or other

appropriate strategic time frame)? How does it plan to review those in the

light of changing business climates?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the business's main

competitors?

- What are the strengths, weaknesses and aspirations of the business's

main collaborators?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the business's main clients?

- What are the business's own relative strengths and weaknesses?

(d) Does the business understand which unwritten traditions, of its

own, its market or its professional speciality, help it to operate and which

restrict its success?

- What percentage of the business's current income is derived from its

original business sectors and services?

- Has the business made an assessment of the possible changes in demand

for those services over the next strategic period?

- Has the business assessed whether there is a changing demand for its

services and whether there is a presumption that clients will continue to

value the same expertise as they have previously done?

- Has the business evaluated the need to acquire new skills and

knowledge?

Some of the tools available to assist in answering the questions in

section 3.2 are:

(a) STEPE Analysis

STEPE is a formal framework for reviewing the external environment. It

involves considering a range of external issues which might impact upon the

business. This STEPE analysis can be used to help map the (S) Social (T)

Technological (E) Economic (P) Political and (E) Environmental influences on

the organisation and enables an assessment to be made of their likely impact

on the business. For example, how important is each trend and independently

how certain/uncertain are you about each trend? This type of analysis offers

some initial views on the significance of the changes taking place at

present, and for the future.

(b) SWOT Analysis

SWOT is a further analysis technique which enables the performance of the

organisation to be assessed in terms of both internal factors, that is its

(S) strengths and (W) weaknesses; and externally in terms of the (O)

opportunities available/open to it and the (T) threats confronting it. Again

this initial assessment can be of considerable value in identifying some of

the strategic choices facing the business.

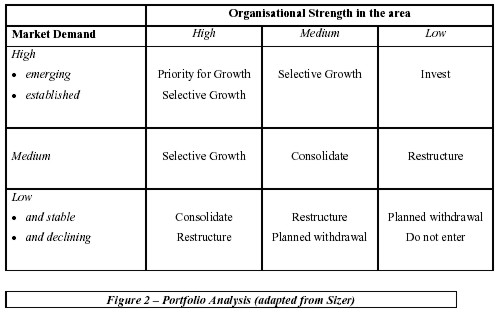

(c) Portfolio Analysis

This technique can be helpful, particularly for evaluating and reviewing

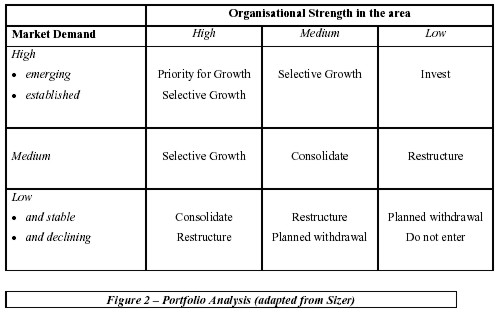

product and service portfolios. Such a portfolio analysis might involve a

review as illustrated by Figure 2 where the different products/ services are

positioned in relation to subject strength and market demand.

In addition to portfolio analysis this perspective also emphasises the

importance of 'differentiation' to highlight what is distinctive about an

organisation compared to rival organisations. Porter (1996) suggests that

'you can only outperform rivals if you can establish a difference that you

can preserve'. He also distinguishes between differentiation based on

'operational effectiveness' and that based on 'strategic positioning'. For

Porter, 'operational effectiveness' implies performing similar

activities

better than rivals can perform them, whereas 'strategic positioning'

means performing different activities from rivals or performing

similar activities in different ways from rivals.

The references contain more information on each of these

tools.

A further process which might also feature highly when using

these tools would be to review the market sectors in which the organisation

has developed a reputation together with a review of the key

stakeholders/client groups who are of critical importance to the

organisation in each sector. This analysis will assist in prioritising the

different areas for investment.

The result of the strategic planning process should be a

written plan encapsulating a Mission Statement and the other elements listed

in section 3.2. It is vital that all owners/ managers feel ownership of the

plan and its contents, and that it is regularly and widely used to inform

business decisions and as the benchmark for reviewing organisational and

individual performance.

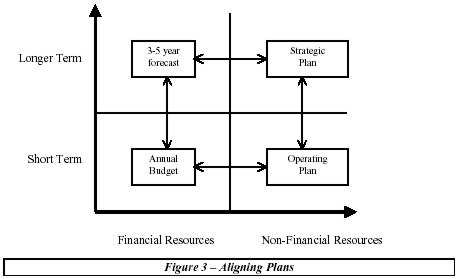

The process of taking the creative ideas which emerge during

the planning process and turning these into effective operational plans also

requires careful thought, particularly to minimise any lack of integration.

Broadly speaking, the parts which need linking together include;

-

The statements which clarify and make explicit the

overall direction, i.e. 'the strategy' for the organisation;

-

The processes and statements used to manage financial

resources, i.e. 'the budget' for the organisation;

-

The processes and statements which describe specific

actions to be undertaken across the organisation, i.e. the 'operating

plan' for the organisation; and

-

The processes and documents which are used on a

one-to-one basis to summarise the priorities and objectives for staff

across the organisation i.e. the 'performance appraisal and rewards'

system.

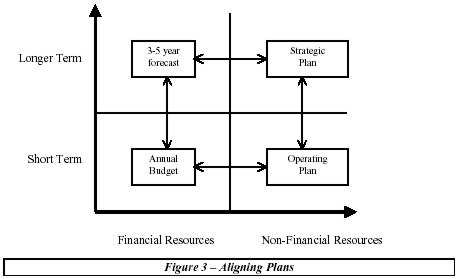

Figure 3 illustrates the links between the first three of

these elements.

A key component in the creation of an effective Operating

Plan is a method of translating general statements of intent (from the

Strategic Plan) into specific objectives and actions. Whether at the level

of objectives for the organisation or for individuals, it is important to

ensure that clear measures of success exist, with clear lines of

accountability. It can be useful to review objectives against the following

SMART framework to confirm that they are:

| S |

Specific - Is the objective specific enough, or should

we break it down into more manageable parts? Have we clearly specified

who is accountable? |

| M |

Measurable - have we considered what direct and indirect

measures could be used to assess whether progress is being made? |

| A |

Action oriented - Have we identified clear actions which

need to be progressed? |

| R |

Resourced - Have we fully considered the resource

implications of the objective? |

| T |

Timed - Have we clarified the time limits for

achievement of the objective? |

The STAIR test (Grundy, 1995) can also be a useful means of

cross-checking that the objectives are appropriate:

| S |

Simplistic - Is this objective sufficiently demanding? |

| T |

Tactical - Is this objective tactically relevant and we

have considered how it fits in with other tactically similar objectives? |

| A |

Active resistance - Have we fully considered the impact

of this objective on others? |

| I |

Impractical - Have we fully considered the

practicalities of implementing this objective (within the allocated

time)? |

| R |

Risk - Have we fully explored all of the potential risk

factors? |

The result of this discussion and testing will be a list of

specific, operational objectives, with responsibility for each one assigned

to an individual, named manager. These form one heart of the Operating Plan.

The second heart is the annual budget, appropriately subdivided to work

areas, which allocates the resource needed for completion of the objectives.

Iteration will be needed to ensure compatibility between targets and

finances, both prior to the start of the plan period and also during the

year. The two elements must be altered in a coherent and coordinated manner

if the business if to achieve the maximum possible level of success with the

resources available to it.

Once again, the references at the end of this chapter

provide further information in this area.

The time and effort required to monitor performance against

plans is probably the area where most planning processes have the greatest

difficulty. All too often, those responsible for planning fail to recognise

the amount of time and energy which is required to establish processes and

procedures to monitor and review plans on a regular basis. How often does

the plan become a filed document which is rarely examined again until the

next planning period? To avoid this, it is vital that well-established

processes are documented and time set aside to review, learn from and update

the plans.

It is often said that 'what gets measured gets done' and 'if

you can't measure it, you can't plan it'. Clear measures are essential in

monitoring progress against the plan. Targets, however, also have the

potential to confuse - it is therefore essential to have a manageable number

of clear, concise targets which are regularly monitored. Two frameworks

which will be useful in this area are outlined below.

(a) The Balanced Scorecard

The concept of a 'balanced scorecard' (Kaplan and Norton,

1996) of performance measures is one which has become fashionable in recent

years. This framework has emerged to emphasise the need in the business

environment to ensure that adequate attention is given to factors beyond

purely financial measures. To balance financial measures, it is also

necessary to have measures which focus on people, systems and the market.

The challenge is usually to select those performance

measures which are of most significance, and for which robust data

collection and analysis techniques exist to enable them to be monitored on a

regular basis. In so many cases, the measures selected are not linked to the

overall strategy of the organisation and often suffer because of a lack of

comparative data.

The contents of the scorecard must truly reflect the

strategic vision of the organisation.

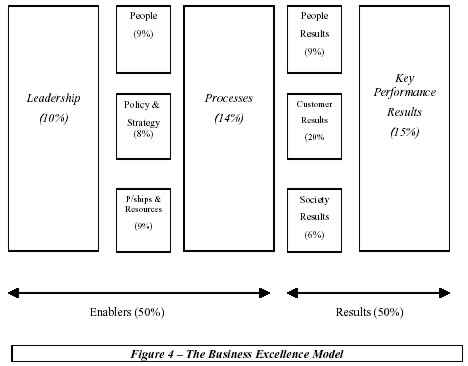

(b) Business Excellence Model

A further formal, analytical framework is the 'Business

Excellence' model developed by the European Foundation for Quality

Management (EFQM). The purpose of this model is to enable a consistent

measurement methodology to be utilised across organisations. It therefore

enables comparative benchmarking.

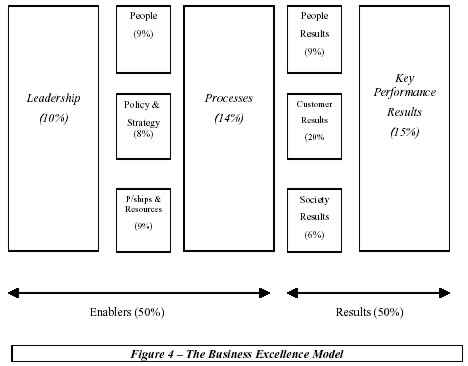

The model (see Figure 4) sets out the areas which must be

addressed by planning targets; the percentages are the weightings generally

given to these areas in quality awards. Further information on the model is

available from the EFQM web site at

www.efqm.org, which includes clear definitions of each of the elements.

In addition to monitoring progress against objectives (and

adjusting business activity accordingly), the business will need robust

accounting systems and procedures to provide both the financial accounts

required by auditors etc, and the management accounts needed within the

business.

The sections above have suggested various techniques to

facilitate business planning, something which is vital for sustained

business success. In successful planning and monitoring, however, systems

alone cannot deliver high performance. They need to be embedded in the

culture of the organisation and to involve everyone. Leaders must be

responsible for setting the high level, bold aspiration for the organisation

and relentlessly communicating it to staff. Managers at all levels must be

involved in regular and rigorous review of performance against expectations.

Staff must be rewarded in relation to the contribution they make to

achieving the organisation's objectives. And customer consultation and

feedback provides a vital 'reality check' on whether the organisation is

delivering the services that matter to them, to a standard that they expect.

Only with such embedding will a business properly be linked to the

expectations on it, and properly focus its efforts on what is important.

-

Ensure that your organisation has a structured, regular

approach to strategic and operational planning which involves all staff

and which delivers clear objectives

-

Ensure that the strategic planning process explicitly

reviews the aspirations of each owner/ director/ senior partner with

regard to the company, to ascertain that all key players wish to move in

approximately the same direction at approximately the same speed

-

Place individual responsibility against the achievement

of each target associated with the objectives

-

Regularly monitor progress towards the targets, taking

early and decisive action where necessary

-

Consider how best to link individual staff appraisal and

reward systems to the successful delivery of the organisation's

objectives

-

Christopher, M. and McDonald, M., 1995. Marketing: An

Introductory Text. Palgrave. As the title suggests, a general text

covering the marketing elements of planning.

-

Faulkner, D. and Bowman, C., 1994. The Essence of

Competitive Strategy. Prentice Hall. Provides a general overview of the

subject matter of the chapter.

-

Her Majesty's Treasury, 2000. Public Services

Productivity: Meeting the Challenge. Available from

http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/Documents/

Public_Spending_and_Services/Public_Services_Productivity_Panel/pss_psp_studies.cfm?

Includes straightforward models accompanied by real examples from the UK

public sector.

-

Her Majesty's Treasury, 2000. Targeting Improved

Performance. Available from the same web address as above. Describes a

project to improve Ministry of Defence performance; includes examples of

Missions, targets etc.

-

Johnson, G. and Scoles, K., 1998 (5th edition).

Exploring Corporate Strategy. Prentice Hall. Another general text, at

the next level of detail than Faulkner and Bowman; see particularly

chapters 1 (overview, definitions etc) and 6 (on strategic options).

-

Kaplan and Norton, 1996. The Balanced Scorecard. Harvard

Business School Press. Provides detailed information on this particular

tool.

-

Porter, M., 1996. What is strategy? Harvard Business

Review, November/ December pp61-80. Provokes thought on the subject.

-

Watson, D., 2000. Managing Strategy - A Guide to Good

Practice. Open University Press. A general overview of the subject

4. Quality and

Customer Service

As has been mentioned several times in chapters 2 and 3,

customers are of paramount importance to businesses. The quality of the

products and services produced by the business and its suppliers determines

whether a customer is happy or not.

Quality can be defined as:

-

Degree of excellence

-

Conformance to requirements

-

Fitness for purpose

-

Meeting agreed client requirements and avoiding problems

and errors while doing so

-

Doing right things right.

The development of a total quality culture throughout the

business must be actively encouraged, to drive the principles of best

practice and customer service. In simple terms, there is a need to 'get it

right first time, every time' if the business is to prosper.

The successful business gives priority to its customers. The

concept of 'customers first', whether they be internal or external

customers, is an ideal goal for all firms. Businesses must always bear in

mind that quality is in the eye of the beholder (the customer). A quality

service is therefore one that satisfies customers' needs.

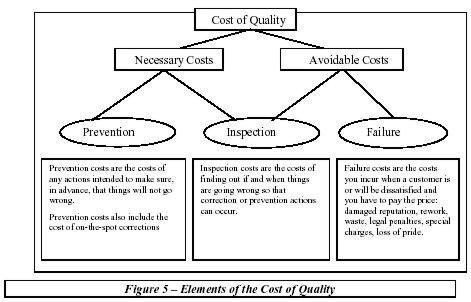

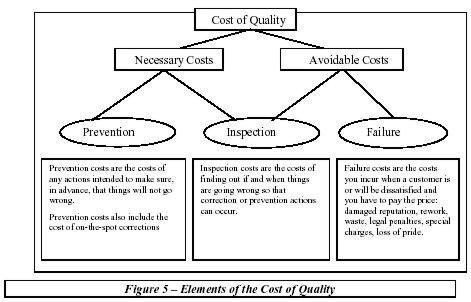

It is not uncommon in service industries like surveying for

the cost of achieving quality to be more than 30% of total revenue of a

business. The cost of quality includes the costs of prevention, of

inspection and of failure. Figure 5 on the following page (with

acknowledgement to ODI) provides more information on this breakdown.

The first step in reducing a business's cost of quality is

to understand that quality costs are not created equal. Rather, they can be

divided into three distinct categories:

-

Prevention Costs - these can be regarded as an

investment because preventing (as opposed to correcting) quality

problems makes the firm much stronger over time.

-

Inspection/Correction Costs - inspecting and checking

other people's work is a role which virtually all managers and

supervisors must fulfil each day. This is despite the fact that neither

the inspector nor the inspected finds this aspect of his or her job

gratifying.

-

Failure Costs - mistakes due to lack of quality that

turn up outside the firm, after a service is delivered to the customer,

are costs that must be avoided. The firm is cast in the worst possible

light when it fails to meet the customers' valid requirements.

In hard monetary terms, failure is by far the most costly

quality problem. The cost of recalling or 'making good' on a service

delivered unsatisfactorily is extraordinarily high.

A rule of thumb for comparing the relative costs of the

three categories in the firm is the "1-10-100 Rule". For every dollar or

hour the firm might spend on preventing a quality problem, it will spend 10

to inspect and correct the mistake after it occurs. If the failure goes

unchecked or unnoticed until after the customer has received the service,

the cost of rectifying the failure will probably be 100 times the cost that

would have been incurred to prevent it from happening at all.

The secret to reducing Cost of Quality is clear: invest

in prevention and ensure that everyone in the firm understands the true

cost of quality. In addition, give people the practical tools they need to

make the 1-10-100 work for, not against, the firm. Ultimately, the key goal

of the firm and each of its members must be to do "right things right".

Quality can only be determined by the customer; ensuring the

regular achievement of quality is therefore about finding out what the

customer wants and the cost that both the customer and supplier can be

satisfied with. The quality of the service that ultimately goes to the

external customer is dependent on how well the internal customer/supplier

chain is managed. It is important for everyone in a firm to identify who

their customers are and how to keep them satisfied. For example, a simple

job being processed through a typical surveying business will contain a

number of steps after instructions are received from the client (external

customer). The steps can range from ensuring all relevant information is

obtained from the client, to searching for information, to collating the

information, to undertaking a survey, to drafting plans and field notes, to

checking and writing correspondence. Each of these steps can be undertaken

by a different person (internal customer).

A number of people from within the organisation and beyond

have some input into the final product. The quality of the final product or

service is only as good as the weakest link. If, for example, the obtaining

of a piece of vital information was overlooked then the survey may be

incorrect. This may result in complete failure of the job at a later stage

or even repetition of some work, costing the organisation (or the client) an

added amount. This type of failure may occur at any step in the processing

of the job through the organisation. It is better to invest in preventing

such a failure from occurring (for instance through training) than incurring

the cost of failure when there is a breakdown in the process. A key to

overcoming this is for everyone in the organisation to know where they stand

in the process. When a problem is identified that may affect quality then

every employee, no matter where they stand in the organisation, must act to

ensure that the chance of failure at a later stage is minimised or removed.

FIG has adopted a Charter for Quality in which its members

recognise and agree to undertake:

-

"To commit our respective organisations and member

associations to quality, service and client/customer satisfaction;

-

To develop a total quality culture through management

commitment and leadership within our organisations;

-

To develop a continuous improvement approach to all

our activities;

-

To work towards achieving recognition of our

respective organisations to internationally recognised standards for

quality systems;

-

To encourage the suppliers of products and services

to surveyors to embrace the principles of the quality movement;

-

To train surveyors through a total quality approach;

and

-

To share and participate in benchmarking and

performance measurement."

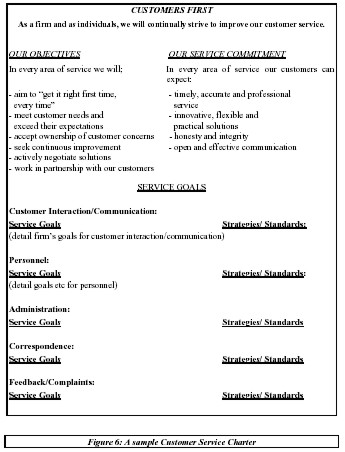

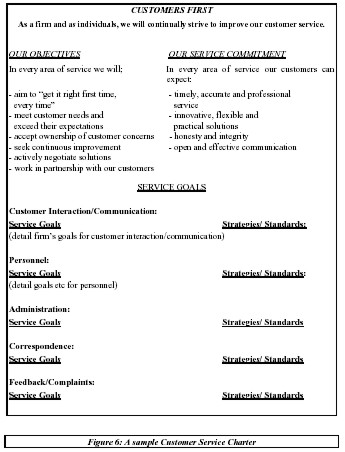

It is important for staff within a firm to make a commitment

to customer service. An ideal way is to develop a customer service charter

which incorporates services objectives and service commitment, followed by

service goals, strategies and standards.

An example of such a charter is at Figure 6. Goals,

strategies and service standards will vary from firm to firm and in

different parts of the world. Very simple mechanisms can be extremely

effective, for instance a visitors' book with space for comments, or a

simple questionnaire to be included with invoices.

A key element of customer service is providing the customer

with assurances as to the quality of the products and services supplied. The

International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) has developed a series

of standards (ISO 9000 series) which contain guidelines to allow the

development of an appropriate quality management system which can do this.

The latest ISO 9001 (2000 version) addresses a number of

inadequacies in the way quality assurance has been seen in the past.

Properly understood, ISO 9001 asks firms to address a number of basic

management issues in a manner that is appropriate to the nature of the firm

in question. The issues themselves are virtually indisputable in terms of

ensuring good service to clients and the ongoing health of the firm.

ISO 9001 (2000 version) is very relevant from a surveying

business's point of view because, as a technical profession, surveyors'

weaknesses have tended to arise in relation to broader management controls.

Successful organisations have a focus on business planning, communication

and the image they project to the community.

In a typical surveying practice, ISO 9001 suggests that

management should:

-

Communicate well with clients and record their

requirements;

-

Actively manage staff and resources to ensure that

deadlines are met;

-

Make sure that staff understand their roles and

responsibilities within the firm;

-

Plan work processes to ensure clients' technical

requirements are satisfied;

-

Check and authorise all work prior to release;

-

Ensure that staff are adequately trained;

-

Confirm that measuring equipment is working within

specifications;

-

Ensure that subcontractors work to equivalent standards;

-

Review procedures to ensure that they are being followed

by staff (and are cost effective); and

-

Have a well organised and secure records system

(including computerised records).

ISO 9001 therefore provides an ideal framework for

considering, implementing and monitoring the important management issues of

any business, but it does require time and resources to make it happen. It

is a most useful tool to use as a framework for a critical evaluation of a

firm's organisational processes.

The implementation of quality customer service as part of

the road to continuous business improvement can be considered in three

stages.

| Stage 1: |

Creating the Environment for Quality

(creating a controlled and systematic way of doing business with

quality aware and committed people). |

| Stage 2: |

Quality Improvement

(seeking out ways to improve existing processes and reduce the cost of

problems). |

| Stage 3: |

Continuous Business Improvement

(achieving sustainable, continuous improvement of all processes,

products and services through the creative involvement of all people). |

In a competitive market place, it is rarely wise to stand

still and give competitors the opportunity to race past you. Hence, it is

worth remembering that quality is a journey not a destination, and that it

is an ongoing process that should never end.

Using ISO 9001:2000 and having a Customer Service Charter

provides an ideal framework to demonstrate to customers that the firm does

value its customers and wants to provide the best service possible.

-

Create an environment of quality and customer service

and continuously review how to embed this in the business

-

Ensure that all staff are adequately trained

-

Document key processes and ensure that staff follow

them; this will ensure consistency of activity and of output, providing

assurance to customers

-

Undertake customer surveys to determine their needs and

expectations so that the business can plan to meet and exceed them

-

Continually review all activity to ensure best practice,

involving staff and customers in this process

-

Dale, D. G., 1999. Managing Quality. Blackwell. A

thorough text on the subject.

-

Department of Treasury and Finance, Victoria, Australia,

June 1995. Customer Service Commitment Charter. An example in this area

-

Leland, K. and Bailey, K., 2000. Customer Service for

Dummies. Hungry Minds Inc. An easy-read but valuable exploration of the

subject.

-

Parker, J., 2000. Quality Awards and Surveyors.

Proceedings of the FIG Working Week, Prague. A general overview of the

subject.

-

Tricker, R., 2000. ISO9001: 2000 for Small and Medium

Businesses. Butterworth-Heinemann. An excellent text covering quality

management systems as well as the requirements of ISO9001.

We should try to attempt, before going any further, to

define what ethics are. The following are from sources as diverse as the

Oxford English Dictionary, the New Zealand government and a business ethics

textbook:

-

'What ought to be; the ideals of what is just, good and

proper'

-

'In essence, ethics is concerned with clarifying what

constitutes human welfare and the kind of conduct necessary to promote

it'

-

'The department of study concerned with the principles

of human dignity'

-

'Giving of one's best to ensure that clients' interests

are properly cared for, but that in so doing the wider public interest

is also recognised and respected.'

Why are ethics important to a surveying firm? At the most

fundamental level, perhaps, they are important because companies (and

individuals) with clear values, and who apply those values consistently,

will be more successful than companies without such clarity. This is because

they will not put themselves in positions which later become compromising

and need time and effort to resolve. This assertion is supported by a number

of studies. In short, principled decision making is compatible with

profitable decision making.

That this should be so is perhaps clear from the issues

referred to in earlier chapters of this Guide - the public and society have

expectations of professionals and are proving more and more willing to

demand remedial action where unethical decision-making seems to be taking

place. A professional is expected to balance the needs of a client and of

society at large, thus placing an additional dimension on the

decision-making process.

The profile of many decisions by surveying firms may be

higher than those of other professionals because of the large number of

survey decisions which impact directly on the environment, an issue

surrounded by public concern and protected by high profile pressure groups.

If ethical decision-making is compatible with business

success, and such decision-making requires consistent application of a

defensible set of values, it is evident that every survey firm requires a

clear set of values and procedures that ensure consistent application of

them by every individual in the firm. Unsurprisingly, therefore, this area

has been the subject of a variety of work by professional bodies such as FIG

and national survey associations. Most survey associations will have model

guidelines for firms, which pay particular regard to national priorities and

laws. The FIG work had the aim of providing a framework for national and

individual work. FIG Publication No 17 (Statement of ethical principles and

model code of professional conduct) sets down four ethical principles:

-

Integrity;

-

Independence;

-

Care and competence; and

-

Duty.

The text of the publication is reproduced for easy reference

in the Appendix to this Guide.

These principles will need to be considered in relation to a

number of roles of the surveyor:

-

As an employer;

-

As a supplier;

-

As a professional adviser;

-

As a member of a professional body;

-

As a business practitioner; and

-

As a manager of a range of resources.

FIG Publication No 17 outlines the key areas within each

role, and provides guidance on each of them. As with issues covered earlier

in this Guide, it is vital that the owners and senior managers of the

organisation all espouse similar priorities in this area, if a clear lead is

to be given to staff and a clear message to customers and other interest

groups.

5.3 A code of conduct for the

business

The need for every firm to have procedures for applying its

values can be summed up as follows: 'imagine yourself in a jungle. A guide

is essential, whereas a map is useless as you don't know where you are

starting from'.

There are, however, some pitfalls to be avoided when setting

down a code:

-

The emphasis must remain on providing frameworks which

can guide actions - any attempt to provide a comprehensive list of do's

and don'ts, covering every conceivable situation, will fail as a

situation not covered will arise!;

-

Actions are much more significant in determining ethical

culture than any code. The codes will not gain ownership unless the

owners and directors of a business are seen to be living by them; and

-

The codes must be carefully thought-out, with employees

being involved in their development, rather than knee-jerk reactions to

particular crises. The need for wide involvement is particularly

important in partnerships (a common business form for professionals), as

partners have greater freedom of action (and expectation of input) than

employees generally do.

Successful codes will, therefore, contain text such as 'we

must maintain in good order the property that we are privileged to use,

protecting the environment and natural resources' (from Johnson and

Johnson's Credo) and 'surveyors [must] avoid any appearance of professional

impropriety' (from the FIG Model Code).

What should be in a firm's ethical code? Section 5.2 above

suggests the general principles and roles that should be covered. Trying to

be more specific, the RICS Guidance Notes on Professional Ethics suggest

that clear guidelines need to be provided on the following topics:

-

Gifts, hospitality, bribes and inducements;

-

Health and safety;

-

Equal opportunity, discrimination and sexual harassment;

-

Conflicts of interest;

-

Insider dealing;

-

Money laundering;

-

Disclosure of confidential company information;

-

Financial transactions;

-

Fair competition;

-

Alcohol and drug abuse;

-

Whistle blowing;

-

Non-executive directors;

-

Copyright and ownership of files;

-

Standards in advertising;

-

Protection of the environment;

-

Relations with local communities; and

-

Political and social behaviour.

This should perhaps be regarded as a 'long list' of topics

that should be considered - not all subjects will be relevant for all firms,

and the profile and priority of the different items will differ between

countries and firms. Always bear in mind, however, the need to have

guidelines in place before an issue faces the firm, not to react when

something occurs.

We can consider the application of a code by an individual

member of staff in a particular set of circumstances as a filtering process

- the code is more likely to tell the individual how not to act than it is

to define how to act. There will be a number of filters at work. The

relative importance of these filters is likely to vary around the world -

organisational culture is, for instance, likely to be strong in the east,

and personal values strong in the west. It is therefore important that firms

take full account, when drawing up a code, of the likely issues in the

different regions in which they are likely to operate - bribery will be a

far more real issue in some countries than others, for instance.

An individual will, in a particular set of circumstances,

use the different filters to determine his or her course of action. The

relative priority of the filters becomes crucial when the answers from the

different filters conflict. In almost all cases (although less heavily in

eastern countries), personal values will be the strongest filter. Given that

many decisions will have to be taken by an individual without reference to

colleagues (and, indeed, without access to the text of the firm's ethical

code), the owners and directors of a firm need to have confidence in how the

individual will react. In an extreme case, if organisational and individual

values are too greatly in conflict, the continued employment of the

individual by the firm becomes a real issue, so this is an area which needs

to be covered when recruiting staff: the firm will generally be (rightly)

held to account for the actions of an individual member of staff.

It is, of course, a dangerous policy to leave the testing of

a code's application until the moment when it is necessary 'for real' - knee

jerk responses are likely to be a dangerous way of creating policy and

reputation.

A helpful way of testing the clarity of a code, and

cross-checking it against an individual's decision-making process, is to

discuss the issues in advance. A useful technique, to ensure that the

discussion is grounded in reality rather than vague principles, is to use

examples as the basis for the discussion. A variety of examples have been

created for this purpose; they should, for best effect, be tailored to the

circumstances of the firm and the individuals in it, drawing on real

experiences that people in the firm have encountered. The FIG Working Group

on Business Practices created three dilemmas as part of its work; they

produced a range of responses from professional surveyors around the world.

They are reproduced here as a starting point in a firm's creation of such

dilemmas:

-

Whilst undertaking a site survey for a private sector

client, it becomes apparent to you that the client intends to ignore

potentially serious environmental impacts of the development of the

site. You reflect on your obligations to your client and to the

community. What do you do?

-

As a partner in a firm of surveyors, you have

successfully won a tender for some work in a country where bribes are

considered a normal part of doing business,. In your own country, bribes

are illegal (or, at the very least, not accepted practice). Will you use

bribes to get the project completed successfully?

-

You have successfully tendered for a survey. Other work

means that you cannot complete the work by the required date, so you

subcontract the work to another surveyor who only charges you a small

fraction of the fee you have agreed with the client. What do you charge

the client?

Such dilemmas have proved to be a valuable tool in the

development of a firm's code of ethics, and in the ongoing development of

the code and of employees' understanding of it. This dialogic approach is

not a luxury to be taken up by a firm if individuals are interested or if

time permits - it is an essential part of running a firm, as essential as

the continuing professional development of individuals' technical skills and

technological knowledge.

Professional ethics are becoming increasingly important.

Consistent application of clear and defensible values is compatible with

business success and will avoid decisions by individual members of staff

which are catastrophic for the reputation of a firm: a reputation which has

taken years to build can be shattered in a moment.

A code of conduct is therefore a vital part of a firm's

'handbook'. Such a code needs to be created with the involvement of staff

and everyone's understanding of it needs to be continually tested - and not

through real situations! The code needs to cover the principles to be

applied in the full range of situations that employees of the firm are

likely to encounter. An individual's values will generally predominate over

the code, hence the values of an individual need to be tested during the

recruitment and development process.

A variety of material is available to a surveyor starting up

or taking over a survey firm. This includes the FIG Code of Ethics at the

Appendix to this Guide, and guidance from national survey associations. Such

guidance will provide a valuable framework for the firm's code, but it is

vital that there is clear ownership of the firm's code by the firm and its

staff - fully off-the shelf codes will not work.

-

Create an initial code of conduct for the firm as soon

as you start to build the firm. Use frameworks available from national

survey associations and other firms but tailor them to your firm and its

circumstances

-

Continually test the code against situations that you

are likely to encounter, and develop it as necessary. Do this thoroughly

at least once a year

-

As part of staff development processes, discuss ethical

dilemmas to ensure the conformance of individuals with the code

-

Chrysalides, G.D. and Kaler, J.H., 1993. An Introduction

to Business Ethics. Chapman Hall. A general text on the subject.

-

Davies, P. W. F., 1997. Current Issues in Business

Ethics. Routledge Publishing. A number of short essays on key topics -

see particularly chapters 4 (on business and social responsibility), 7

(on ethics for professionals) and 8 (on codes of ethics).

-

Greenway, I., 2000. Practical Aspects of Ethics.

Proceedings of the FIG Working Week, Prague. Contains an overview of

ethical theory and some survey-related dilemmas.

-

Hodgson, K., 1992. A Rock and a Hard Place: How to Make

Ethical Business Decisions when the Choices are Tough. ACACOM Books. A

general text; see particularly chapter 9 on cultural differences.

-

Hoogsteden, C.C., 1994 (1). The Ethical Attitudes of

Professional Surveyors in New Zealand. Proceedings of the XX FIG

International Congress, Melbourne. A paper highlighting the perceived

decline in professional standards and proposing some remedial actions.

-

Hoogsteden, C.C., 1994 (2). Ethics Education for

Tomorrow's Professional Surveyors. Proceedings of the XX FIG

International Congress, Melbourne. Raises the issues concerning the

necessary education in this area for students of all ages.

-

Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, 2000. Guidance

Notes on Professional Ethics. RICS. A framework helping businesses to

develop their own codes.

-

Trompenaars, F, 1993. Riding the Waves of Culture:

Understanding Cultural Diversity in Business. Nicholas Brealey

Publishing, London. Focuses particularly on differences between

cultures, with much empirical research.

6. Managing

Information and Information Technology

Information is a vital part of every manager's job. For

information to be useful, it must be accurate, timely, complete and

relevant.

Information technology systems provide the hardware for

managing information. They contain five basic components:

-

An input medium;

-

A processor;

-

Storage;

-

A control system; and

-

An output medium.

Although the form varies, both manual and computerised

information systems have these components. Many organisations now use a

combination of systems software and applications software to perform key

business functions, and constantly seek greater integration across these

systems.

An organisation's information technology requirements are

determined by four factors. Two general factors are the environment and the

size of the organisation. Two specific factors are the area and level of

different users and groups of users within the organisation. Each factor

must be considered in planning an information system.

There are four basic kinds of information system:

-

Transaction-processing systems;

-

Basic management information systems;

-

Decision support systems; and

-

Executive information systems.

Each provides certain types of information and is most

valuable for specific types of managers. Separately and together, such

systems deliver business intelligence - the processes and technology

necessary for today's business environment.

Managing information systems involves three basic elements:

Information systems affect organisations in a variety of

ways. Major influences are on performance, on the organisation itself, and

on behaviour within the organisation. There are also limitations to the

effectiveness of information systems. Managers should understand these

limitations so as not to have unrealistic expectations. It is also important

that managers deal explicitly with the issues that changes in workplace

technologies can create, and actively facilitate change.

Recent advances in information technology include

breakthroughs in telecommunications, networks and expert systems. Electronic

commerce is a rapidly growing area, and is the conduit for an increasing

share of global business transactions. The Internet and internal company

intranets are playing increasingly important roles. Clearly, such advances

will continue to enhance an organisation's ability to manage information

more effectively. The increasing rate of change, however, emphasises the

need for organisations to keep abreast of developments, and of the

opportunities and thrusts that they create, so as to make appropriate

business decisions on investments.

6.2 Managing information

technology strategically

Managing IT strategically in an organisation is necessary if

the organisation is to be effective and efficient in the use of its IT

resources. Managers, by referencing the principles set out in this chapter

when making IT-related decisions, will contribute to an emerging strategic

alignment that will culminate in more efficient systems and, as a result,

improved service and product delivery to the organisation's customers.

This section also describes processes for review, and

principles to facilitate changes as the organisation and external

environments change. This orientation-based approach has been described,

rather than the more traditional linear planning models, to provide

decision-makers with maximum flexibility to take initiatives, while at the

same time providing a workable, flexible and robust framework that will

foster organisational efficiency. The value it adds to the organisation's

operations lies in its articulation of principles for management

decision-making. Its success will depend on the consistency with which the

principles are applied.

6.2.1 Investment Principles

The following principles need to be applied when considering

investments in information technology.

-

An organisation invests in Information Technology to

support activities that generate outputs which meet the organisation's

objectives - this addresses the fundamental, underlying purpose for

choosing to invest in technology. The principle makes clear that

technology is not to be pursued as an end in itself. Rather, technology

only exists to support the organisation in achieving its desired

outcomes.

-

An organisation uses consistent business case and

project management processes to assess and implement all proposals -

this is to confirm that established frameworks and processes are used to

guide investments and to provide managers with a basis for comparing

proposals and projects. Project management standards help to ensure that

investments are translated into outcomes that are delivered on time and

within budget.

Business cases, investment appraisal and project management

frameworks and processes should be used to guide and monitor IT investment

decisions. Business plans should include substantial treatment of IT

matters. These plans will form the backdrop against which initiatives and

proposals involving technology will emerge. In the same way that workforce,

risk, financial, and other planned operating parameters are assessed and

prioritised by management, technological development will grow from planning

predicated on business drivers. This will ensure that IT is used as a means

to an end (that end being business success).

6.2.2 Infrastructure Principles

There are five principles that can be adopted to describe

the setting for an organisation's Information Technology infrastructure.

These are:

-

An organisation reviews and defines its systems

architecture annually and creates plans for the next two generations.

-

An organisation's work areas and service providers are

responsible for ensuring that systems are fully compatible with the IT

systems architecture.

-

An organisation grows its network to meet the needs of

businesses/users by:

-