| |

FIG PUBLICATION NO. 77

Good Practice or Resilience Planning to Address Water

Governance Challenges in Africa

FIG Commission 8 - Spatial Planning and Development

Working Group 8.5 on African Water Governance

FIG REPORT

Primary Author:

Prof. Richard Pagett

Co-Authors:

Prof. Isaac Boateng

Prof. Kwasi Appeaning Addo

Dr. Philip-Neri Jayson-Quashigah

Dr. Kofi Adu-Boahe

PREFACE

Water is an indispensable resource for society, yet it can also pose

threats such as floods or droughts. Water governance seeks to enhance the

equal, efficient, and effective distribution of water resources and balances

water use between socio-economic activities and ecosystems. Political,

social, and economic arrangements can govern the process of water

management, which becomes more and more urgent given the impact of climate

change and the need for sustainable development.

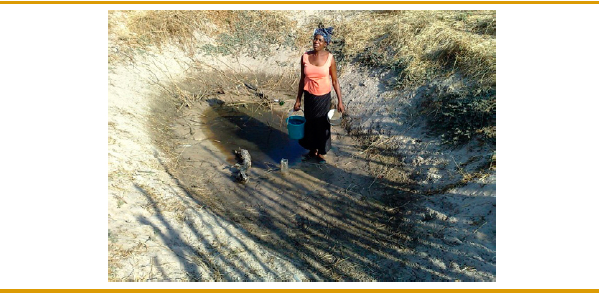

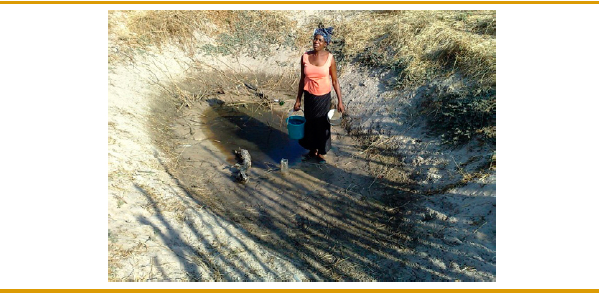

FIG Commission’s 8 Working Group 8.5 about African water governance has

delivered a report addressing the challenges of water governance in

urbanised areas in Africa. Lack of water is impacting the ecology,

agriculture, and the general economy of most African nations. In addition,

poor water governance results in inequitable access to freshwater and

unsustainable water usage in many parts of Africa.

It is the purpose of FIG and its Commission 8 to assist the surveying

profession in all aspects of spatial planning and development. This report

considers some of the social, environmental, political and economic context

of water governance in Africa to identify the strategies necessary in terms

of resilience, in the face of climate change, population growth and

diminishing resources. Cross-cutting socio-economic, systemic and policy

challenges in water governance are analysed and critical success factors for

managing water resources in Africa are described. In response to the

expected impact of climate change the need for strategies to enhance future

resilience in water governance is apparent.

This publication of FIG Commission 8 further contributes to seek

sustainable pathways for water governance from the broader perspective of

spatial planning. The report should help government, decision makers and

professionals in Africa and beyond to respond to the major challenges of

sustainable water governance, both qualitative and quantitative.

FIG would like to thank the members of the working group and the

specialists who have contributed to this publication for their constructive

and helpful work.

Marije Louwsma

Chair of FIG Commission 8, 2019–2022

Introduction

Environmental change as a result of climate change, population growth and

desertification is affecting water systems significantly in Africa. Lack of

water is impacting the ecology, agriculture and the general economy of most

African nations. In addition, poor water governance results in inequitable

access to freshwater and the unsustainability of its use in many parts of

Africa. Water governance refers to a range of political, social, economic

and administrative systems that are in place to develop and manage water

resources and the delivery of water services, at different levels of society

(UNDP 2004). It has also been defined as a set of rules, practices, and

processes (formal and informal) through which decisions for the management

of water resources and services are taken and implemented, stakeholders

articulate their interest and decision-makers are held accountable (OECD,

2015a). Water governance addresses issues on who gets what water at what

quality and quantity, when and how, and who has the right to water and

related services, and their benefits as well as dealing with the challenges

in water delivery at all levels. Effective water management determines the

equity and efficiency in water resource and services allocation and

distribution, and balances water use between socio-economic activities and

ecosystems (Milligan, 2018).

Ensuring the resilience of water governance in Africa is critical as

there is a near consensus that the social and ecological impacts of

water-related issues are disproportionately high (Schulze, 2011). The issues

are also worsened by infrastructural deficits, weak institutional capacity

and high political instability in the continent (Bonnassieux & Gangneron,

2011; Spoon, 2014). Sustainable assess to water is still a major challenge

in Africa due to disjointed management arrangements, multiple and divergent

actors’ interests, discordancy between formal and informal water

institutions, the inadequate political will to support water governance, and

uncoordinated water management policies (Lalika et al., 2015; Msuya, 2010).

The need to understand the social, environmental, political and economic

context of water management in Africa requires analysis of current and

future challenges in terms of the resilience of water governance (Olagunju

et al., 2019).

Water used to be the main factor of the location for settlements. It used

to be the key source of transport, agriculture and trade. Therefore,

controlling water resources was a source of power and wealth.

Conventionally, there was no formal regulatory regime for water resources in

most societies of the world. Water resources were governed by

customary/traditional and informal arrangement/ institutional framework. In

fact, water governance was in the hands of the users and this in most cases

led to abuse of water resources and the struggle for control by the user

groups, which often led to conflict (Meissner and Jacobs 2016). Over the

years, it became clear that water is too valuable a commodity for its

management to be handed over to its users and there remains a vital role for

external monitoring and enforcement (DWAF, 1997). This insight brought

governmental, non-governmental and other stakeholder institutions into water

governance. This multi-stakeholder arrangement for water governance emerges

from transboundary water governance. These multiple institutions mostly act

as monitors and enforcers of bilateral or multilateral water governance

regulatory policies. The water resource community in these instances

includes the governmental and private sectors, water managers, users and

civil society implementing transboundary water management strategies

(Meissner and Jacobs 2016). This ‘community’ also develops solutions to

water management challenges.

According to Norman and Bakker (2009), the water governance literature

describes governance based not on political borders but on natural

catchments and encourages multi-sectoral approaches like Integrated Water

Resource Management (IWRM). International river basin organisations and

commissions have become common institutional forms that manage water. These

organisations are set up with the aim of fostering basin-wide cooperation

(Mirumachi and Van-Wyk, 2010). Institutional mechanisms, such as

co-management, public-private partnerships and social–private partnerships

are among the conventional ways in which the state, users and communities

interact to manage water resources (Lemos and Agrawal, 2006). In recent

times, water governance has become a global issue due to water scarcity,

water resource crises in some part of the world, climate change, global rush

for land and water and power shifts in the global political economy (Sojamo,

and Larson, 2012). In addition, rapid economic development and societal

change are putting increasing pressure on water ecosystems and other natural

resources (Batchelor, undated; Baumgartner and Pahl-Wostl, 2013). In many

countries or regions, demand is exceeding supply to the extent that water

resources are fully allocated in all, but the highest rainfall years. Under

such conditions, which are often referred to as river basin “closure”,

available water resources are fully allocated and the political importance

of effective water governance increases (Batchelor, undated).

This report considers some of the social, environmental, political and

economic context of water governance in Africa to identify the strategies

necessary in terms of resilience, in the face of climate change, population

growth and diminishing resources.

Chapters

2 Current and Future Challenges in Resilience of Water Governance

3 Principles of Conventional Water Governance and Climate Change Imperatives

4 Current Practice for Managing Water Resources

5 Critical Success Factors when Managing Water Resources

6 Proposals for Future Scenario Strategies for Managing Water Resources

7 Conclusions and Recommendations

Read the full FIG Publication 77 in pdf

Copyright © The International Federation of Surveyors (FIG),

June 2021.

All rights reserved.

International Federation of Surveyors (FIG)

Kalvebod Brygge 31–33

DK-1780 Copenhagen V

DENMARK

Tel. + 45 38 86 10 81

E-mail: FIG@FIG.net

www.fig.net

Published in English

Copenhagen, Denmark

ISSN 2311-8423 (pdf)

ISBN 978-87-92853-34-9 (pdf)

Published by

International Federation of Surveyors (FIG)

Layout: Lagarto

|